Bloat

By Eclipse.net

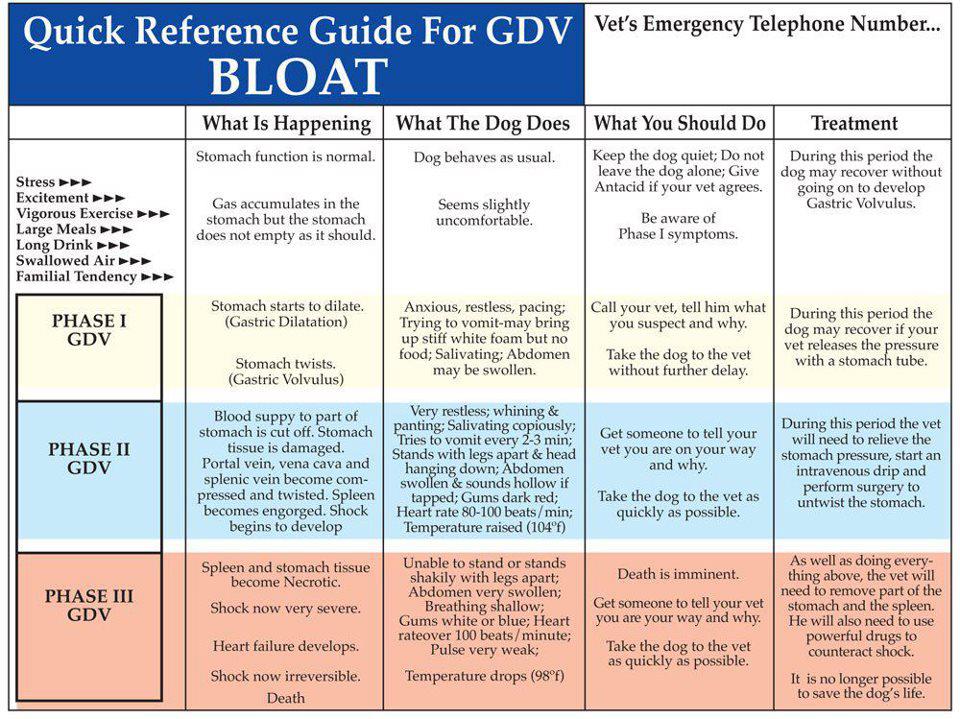

Bloat is a very serious health risk for many dogs, yet many dog owners know very little about it. According to research, it is the second leading killer of dogs, after cancer. It is frequently reported that deep-chested dogs, such as German Shepherds, Great Danes, and Dobermans are particularly at risk. Although we have summarized information we found about possible symptoms, causes, methods of prevention, and breeds at risk, we cannot attest to the accuracy. Please consult with your veterinarian for medical information.

If you believe your dog is experiencing bloat, please get your dog to a veterinarian immediately!

Bloat can kill in less than an hour, so time is of the essence.

Call your vet to alert them you're on your way with a suspected bloat case. Better to be safe than sorry!

The technical name for bloat is "Gastric Dilatation-Volvulus" ("GDV"). Bloating of the stomach is often related to swallowed air (although food and fluid can also be present). It usually happens when there's an abnormal accumulation of air, fluid, and/or foam in the stomach ("gastric dilatation"). Stress can be a significant contributing factor also. Bloat can occur with or without "volvulus" (twisting). As the stomach swells, it may rotate 90° to 360°, twisting between its fixed attachments at the esophagus (food tube) and at the duodenum (the upper intestine). The twisting stomach traps air, food, and water in the stomach. The bloated stomach obstructs veins in the abdomen, leading to low blood pressure, shock, and damage to internal organs. The combined effect can quickly kill a dog.

Be prepared! Know in advance what you would do if your dog bloated.

If your regular vet doesn't have 24-hour emergency service, know which nearby vet you would use. Keep the phone number handy.

Always keep a product with simethicone on hand (e.g., Mylanta Gas (not regular Mylanta), Gas-X, etc.) in case your dog has gas. If you can reduce or slow the gas, you've probably bought yourself a little more time to get to a vet if your dog is bloating.

Bloat is a very serious health risk for many dogs, yet many dog owners know very little about it. According to research, it is the second leading killer of dogs, after cancer. It is frequently reported that deep-chested dogs, such as German Shepherds, Great Danes, and Dobermans are particularly at risk. Although we have summarized information we found about possible symptoms, causes, methods of prevention, and breeds at risk, we cannot attest to the accuracy. Please consult with your veterinarian for medical information.

If you believe your dog is experiencing bloat, please get your dog to a veterinarian immediately!

Bloat can kill in less than an hour, so time is of the essence.

Call your vet to alert them you're on your way with a suspected bloat case. Better to be safe than sorry!

The technical name for bloat is "Gastric Dilatation-Volvulus" ("GDV"). Bloating of the stomach is often related to swallowed air (although food and fluid can also be present). It usually happens when there's an abnormal accumulation of air, fluid, and/or foam in the stomach ("gastric dilatation"). Stress can be a significant contributing factor also. Bloat can occur with or without "volvulus" (twisting). As the stomach swells, it may rotate 90° to 360°, twisting between its fixed attachments at the esophagus (food tube) and at the duodenum (the upper intestine). The twisting stomach traps air, food, and water in the stomach. The bloated stomach obstructs veins in the abdomen, leading to low blood pressure, shock, and damage to internal organs. The combined effect can quickly kill a dog.

Be prepared! Know in advance what you would do if your dog bloated.

If your regular vet doesn't have 24-hour emergency service, know which nearby vet you would use. Keep the phone number handy.

Always keep a product with simethicone on hand (e.g., Mylanta Gas (not regular Mylanta), Gas-X, etc.) in case your dog has gas. If you can reduce or slow the gas, you've probably bought yourself a little more time to get to a vet if your dog is bloating.

Symptoms

Typical symptoms often include some (but not necessarily all) of the following, according to the links below. Unfortunately, from the onset of the first symptoms you have very little time (sometimes minutes, sometimes hours) to get immediate medical attention for your dog. Know your dog and know when it's not acting right. Attempts to vomit (usually unsuccessful); may occur every 5-30 minutes. This seems to be one of the most common symptoms & has been referred to as the "hallmark symptom"

"Unsuccessful vomiting" means either nothing comes up or possibly just foam and/or mucous comes up.

Some reports say that it can sound like a repeated cough

Doesn't act like usual self

We've had several reports that dogs who bloated asked to go outside in the middle of the night. If this is combined with frequent attempts to vomit, and if your dog doesn't typically ask to go outside in the middle of the night, bloat is a very real possibility.

Significant anxiety and restlessness. One of the earliest warning signs and seems fairly typical "Hunched up" or "roached up" appearance. This seems to occur fairly frequently.

Lack of normal gurgling and digestive sounds in the tummy.

Many dog owners report this after putting their ear to their dog's tummy.

Typical symptoms often include some (but not necessarily all) of the following, according to the links below. Unfortunately, from the onset of the first symptoms you have very little time (sometimes minutes, sometimes hours) to get immediate medical attention for your dog. Know your dog and know when it's not acting right. Attempts to vomit (usually unsuccessful); may occur every 5-30 minutes. This seems to be one of the most common symptoms & has been referred to as the "hallmark symptom"

"Unsuccessful vomiting" means either nothing comes up or possibly just foam and/or mucous comes up.

Some reports say that it can sound like a repeated cough

Doesn't act like usual self

We've had several reports that dogs who bloated asked to go outside in the middle of the night. If this is combined with frequent attempts to vomit, and if your dog doesn't typically ask to go outside in the middle of the night, bloat is a very real possibility.

Significant anxiety and restlessness. One of the earliest warning signs and seems fairly typical "Hunched up" or "roached up" appearance. This seems to occur fairly frequently.

Lack of normal gurgling and digestive sounds in the tummy.

Many dog owners report this after putting their ear to their dog's tummy.

If your dog shows any bloat symptoms, you may want to try this immediately.

Bloated abdomen that may feel tight (like a drum) Despite the term "bloat," many times this symptom never occurs or is not apparent;

Bloated abdomen that may feel tight (like a drum) Despite the term "bloat," many times this symptom never occurs or is not apparent;

- Pale or off-color gums-Dark red in early stages, white or blue in later stages

- Coughing

- Unproductive gagging

- Heavy salivating or drooling

- Foamy mucous around the lips, or vomiting foamy mucous

- Unproductive attempts to defecate

- Whining

- Pacing

- Licking the air

- Seeking a hiding place

- Looking at their side or other evidence of abdominal pain or discomfort

- May refuse to lie down or even sit down

- May stand spread-legged

- May curl up in a ball or go into a praying or crouched position

- May attempt to eat small stones and twigs

- Drinking excessively

- Heavy or rapid panting

- Shallow breathing

- Cold mouth membranes

- Apparent weakness; unable to stand or has a spread-legged stance-especially in advanced stage

- Accelerated heartbeat-Heart rate increases as bloating progresses

- Weak pulse

- Collapse

Causes

According to the links below, it is thought that the following may be the primary contributors to bloat. To calculate a dog's lifetime risk of bloat according to Purdue University's School of Veterinary Medicine.

Stress

Dog shows, mating, whelping, boarding, change in routine, new dog in household, etc. Although purely anecdotal, we've heard of too many cases where a dog bloated after another dog (particularly a 3rd dog) was brought into the household; perhaps due to stress regarding pack order.

Activities that result in gulping air

Build & Physical Characteristics

Having a deep and narrow chest compared to other dogs of the same breed

Older dogs

Big dogs

Males

Being underweight

Disposition

Fearful or anxious temperament

Prone to stress

History of aggression toward other dogs or people

According to the links below, it is thought that the following may be the primary contributors to bloat. To calculate a dog's lifetime risk of bloat according to Purdue University's School of Veterinary Medicine.

Stress

Dog shows, mating, whelping, boarding, change in routine, new dog in household, etc. Although purely anecdotal, we've heard of too many cases where a dog bloated after another dog (particularly a 3rd dog) was brought into the household; perhaps due to stress regarding pack order.

Activities that result in gulping air

- Eating habits, especially..Elevated food bowls

- Rapid eating

- Eating dry foods that contain citric acid as a preservative (the risk is even worse if the owner moistens the food)

- Eating dry foods that contain fat among the first four ingredients

- Insufficient pancreatic enzymes, such as Trypsin (a pancreatic enzyme present in meat) Dogs with untreated Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI) and/or Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) generally produce more gas and thus are at greater risk

- Dilution of gastric juices necessary for complete digestion by drinking too much water before or after eating

- Eating gas-producing foods (especially soybean products, brewer's yeast, and alfalfa)

- Drinking too much water too quickly (can cause gulping of air)

- Exercise before and especially after eating

- Heredity-Especially having a first-degree relative who has bloated

- Dogs who have untreated Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI) are considered more prone to bloat. New Gas is associated with incomplete digestion.

Build & Physical Characteristics

Having a deep and narrow chest compared to other dogs of the same breed

Older dogs

Big dogs

Males

Being underweight

Disposition

Fearful or anxious temperament

Prone to stress

History of aggression toward other dogs or people

Prevention

Some of the advice in the links below for reducing the chances of bloat are:

Some of the advice in the links below for reducing the chances of bloat are:

- Avoid highly stressful situations. If you can't avoid them, try to minimize the stress as much as possible. Be extra watchful. Can be brought on by visits to the vet, dog shows, mating, whelping, boarding, new dog in household, change in routine, etc.

- Do not use an elevated food bowl

- Do not exercise for at least an hour (longer if possible) before and especially after eating. Particularly avoid vigorous exercise and don't permit your dog to roll over, which could cause the stomach to twist

- Do not permit rapid eating

- Feed 2 or 3 meals daily, instead of just one

- Do not give water one hour before or after a meal. It dilutes the gastric juices necessary for proper digestion, which leads to gas production.

- Always keep a product with simethicone (e.g., Mylanta Gas (not regular Mylanta), Phazyme, Gas-X, etc.) on hand to treat gas symptoms. Some recommend giving your dog simethicone immediately if your dog burps more than once or shows other signs of gas.

- Allow access to fresh water at all times, except before and after meals

- Make meals a peaceful, stress-free time

- When switching dog food, do so gradually (allow several weeks)

- Do not feed dry food exclusively

- Feed a high-protein (>30%) diet, particularly of raw meat

- If feeding dry food, avoid foods that contain fat as one of the first four ingredients.

- If feeding dry foods, avoid foods that contain citric acid. If you must use a dry food containing citric acid, do not pre-moisten the food.

- If feeding dry food, select one that includes rendered meat meal with bone product among the first four ingredients.

- Reduce carbohydrates as much as possible (e.g., typical in many commercial dog biscuits)

- Feed a high-quality diet. Whole, unprocessed foods are especially beneficial.

- Feed adequate amount of fiber (for commercial dog food, at least 3.00% crude fiber)

- Add a digestive enzyme product to food

- Include herbs specially mixed for pets that reduce gas

Avoid brewer's yeast, alfalfa, and soybean products.

Promote an acidic environment in the intestine.

Some recommend 1-2 Tbsp of Aloe Vera Gel or 1 Tbsp of apple cider vinegar given right after each meal.

Promote "friendly" bacteria in the intestine, e.g. from "probiotics" such as supplemental acidophilus

Avoid fermentation of carbohydrates, which can cause gas quickly. This is especially a concern when antibiotics are given since antibiotics tend to reduce levels of "friendly" bacteria.

Note: Probiotics should be given at least 2-4 hours apart from antibiotics so they won't be destroyed.

Don't permit excessive, rapid drinking especially a consideration on hot days.

And perhaps most importantly, know your dog well so you'll know when your dog just isn't acting normally.

Breeds At Greatest Risk

Breeds most at risk according to the links below:

Afghan Hound

Airedale Terrier

Akita

Alaskan Malamute

Basset Hound

Bernese Mountain Dog

Borzoi

Bouvier des Flandres

Boxer

Bullmastiff

Chesapeake Bay Retriever

Collie

Dachshund

Doberman Pinscher

English Springer Spaniel

Fila Brasileiro

Golden Retriever

Gordon Setter

Great Dane

German Shepherd

German Shorthaired Pointer

Great Pyrenees

Irish Setter

Irish Wolfhound

King Shepherd

Labrador Retriever

Miniature Poodle

Newfoundland

Old English Sheepdog

Pekingese

Rottweiler

Samoyed

Shiloh Shepherd

St. Bernard

Standard Poodle

Weimaraner

Wolfhound

Sighthound

Bloodhounds

What Is Bloat?

When bloat occurs, the dog’s stomach fills with air, fluid and/or food. The enlarged stomach puts pressure on other organs, can cause difficulty breathing, and eventually may decrease blood supply to a dog’s vital organs.

People often use the word "bloat" to refer to a life-threatening condition that requires immediate veterinary care known as gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV), gastric torsion and twisted stomach. This condition can cause rapid clinical signs and death in several hours. Even with immediate treatment, approximately 25% to 40% of dogs die from this medical emergency.

What Are the General Symptoms of Bloat/GDV in Dogs?

What Causes Bloat in Dogs?

The exact cause is currently unknown. Certain risk factors include: rapid eating, eating one large meal daily, dry food-only diet, overeating, over drinking, heavy exercise after eating, fearful temperament, stress, trauma and abnormal gastric motility or hormone secretion.

What Causes GDV in Dogs?

The exact cause is currently unknown.

What Should I Do If I Think My Dog Has Bloat?

Bring your dog to a veterinarian immediately. Timeliness of treatment is paramount, since a dog exhibiting signs of bloat may actually have GDV, which is fatal if not promptly treated.

When bloat occurs, the dog’s stomach fills with air, fluid and/or food. The enlarged stomach puts pressure on other organs, can cause difficulty breathing, and eventually may decrease blood supply to a dog’s vital organs.

People often use the word "bloat" to refer to a life-threatening condition that requires immediate veterinary care known as gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV), gastric torsion and twisted stomach. This condition can cause rapid clinical signs and death in several hours. Even with immediate treatment, approximately 25% to 40% of dogs die from this medical emergency.

What Are the General Symptoms of Bloat/GDV in Dogs?

- Distended abdomen

- Unsuccessful attempts to belch or vomit

- Retching without producing anything

- Weakness

- Excessive salivation

- Shortness of breath

- Cold body temperature

- Pale gums

- Rapid heartbeat

- Collapse

What Causes Bloat in Dogs?

The exact cause is currently unknown. Certain risk factors include: rapid eating, eating one large meal daily, dry food-only diet, overeating, over drinking, heavy exercise after eating, fearful temperament, stress, trauma and abnormal gastric motility or hormone secretion.

What Causes GDV in Dogs?

The exact cause is currently unknown.

What Should I Do If I Think My Dog Has Bloat?

Bring your dog to a veterinarian immediately. Timeliness of treatment is paramount, since a dog exhibiting signs of bloat may actually have GDV, which is fatal if not promptly treated.

How Is Bloat Treated?

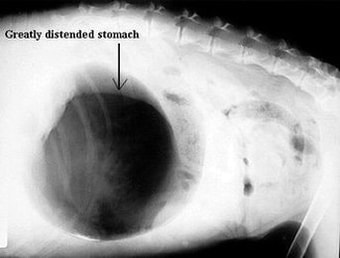

Depending on your dog’s condition, a veterinarian may take an X-ray of the abdomen to assess the stomach’s position. The vet may try to decompress the stomach and relieve gas and fluid pressure by inserting a tube down the esophagus.

How Is GDV Treated?

If the stomach has rotated, emergency surgery is necessary to correct torsion. There are many complications that can occur both during and after surgery, including heart damage, infection and shock; intensive post-operative monitoring for several days is routine. Most vets will recommend that during this surgery, the dog's stomach be permanently attached to the side of the abdominal cavity in order to prevent future episodes.

Are Certain Breeds Prone to Bloat/GDV?

Most dogs love to overeat if given the opportunity, so any dog, from a Greyhound to a Chihuahua, can get bloat.

However, it is very rare for dogs that are not large, deep-chested breeds to be struck with GDV. This condition most often afflicts those dogs whose chests present a higher depth-to-width ratio. In other words, their chests are long (from backbone to sternum) rather than wide. Such breeds include Saint Bernards, Akitas, Irish Setters, Boxers, Basset Hounds, Great Danes, Weimaraners and German Shepherds.

How Can I Prevent Bloat/GDV?

Feed your dog several small meals, rather than one or two larger ones, throughout the day to avoid eating too much or too fast.

If appropriate (check with your vet), include canned food in your dog’s diet.

Maintain your dog’s appropriate weight.

Avoid feeding your dog from a raised bowl unless advised to do so by your vet.

Encourage normal water consumption.

Limit rigorous exercise before and after meals.

Consider a prophylactic gastropexy surgery (which fixes the stomach in place, as described above) if you have a high-risk breed.

Depending on your dog’s condition, a veterinarian may take an X-ray of the abdomen to assess the stomach’s position. The vet may try to decompress the stomach and relieve gas and fluid pressure by inserting a tube down the esophagus.

How Is GDV Treated?

If the stomach has rotated, emergency surgery is necessary to correct torsion. There are many complications that can occur both during and after surgery, including heart damage, infection and shock; intensive post-operative monitoring for several days is routine. Most vets will recommend that during this surgery, the dog's stomach be permanently attached to the side of the abdominal cavity in order to prevent future episodes.

Are Certain Breeds Prone to Bloat/GDV?

Most dogs love to overeat if given the opportunity, so any dog, from a Greyhound to a Chihuahua, can get bloat.

However, it is very rare for dogs that are not large, deep-chested breeds to be struck with GDV. This condition most often afflicts those dogs whose chests present a higher depth-to-width ratio. In other words, their chests are long (from backbone to sternum) rather than wide. Such breeds include Saint Bernards, Akitas, Irish Setters, Boxers, Basset Hounds, Great Danes, Weimaraners and German Shepherds.

How Can I Prevent Bloat/GDV?

Feed your dog several small meals, rather than one or two larger ones, throughout the day to avoid eating too much or too fast.

If appropriate (check with your vet), include canned food in your dog’s diet.

Maintain your dog’s appropriate weight.

Avoid feeding your dog from a raised bowl unless advised to do so by your vet.

Encourage normal water consumption.

Limit rigorous exercise before and after meals.

Consider a prophylactic gastropexy surgery (which fixes the stomach in place, as described above) if you have a high-risk breed.

Here is a product in hopes it may help your dog in case of emergency: https://naturesfarmacy.com/canine/bloat-kits-and-supplies.html

GASTRIC TORSION IN DOGS

by Dudley E. Johnson, M.V.Sc.

Professor of Surgery, University of Pennsylvania

Torsion of the stomach in the dog is characterized by life-endangering distension of the stomach with gas; the stomach is usually found to be severely dilated and congested, and often to have rotated about an axis in the plane of the esophagus.

There are many unknown features of this disease. Even the correct mane for the disease is not known. It is commonly called torsion of the stomach; however, many veterinarians, including the author, believe the primary condition is not torsion, but distension or dilation of the stomach with gas. This distension may or may not be followed by torsion or twisting of the stomach.

Incidence

Torsion of the stomach is seen most commonly in large breeds including the Great Dane and Bloodhound, as well as some of the intermediate size breeds. Most people agree it is a serious problem in the first-two named breeds. There does not appear to be any association with the sex or the age of the animal. It has been reported in young adults as well as fully mature dogs. There is no doubt it can occur suddenly after eating in a previously healthy dog.

The Cause of Torsion of the Stomach

A commonly expressed explanation is that the disease is purely a mechanical twist of the stomach. The stomach, containing some comparatively heavy food material, is pictured as swinging in a pendulum-like fashion. Then, as a result of a sudden jump from a high bench or from rolling or playing, the pendulum is swung completely around the point of fixation of the stomach, the point where the esophagus passes through the diaphragm, giving rise to a twist.

This occludes both the entrance to and the exit from the stomach so that gas, which is produced in the stomach, cannot escape, giving rise to the distension.

Professor of Surgery, University of Pennsylvania

Torsion of the stomach in the dog is characterized by life-endangering distension of the stomach with gas; the stomach is usually found to be severely dilated and congested, and often to have rotated about an axis in the plane of the esophagus.

There are many unknown features of this disease. Even the correct mane for the disease is not known. It is commonly called torsion of the stomach; however, many veterinarians, including the author, believe the primary condition is not torsion, but distension or dilation of the stomach with gas. This distension may or may not be followed by torsion or twisting of the stomach.

Incidence

Torsion of the stomach is seen most commonly in large breeds including the Great Dane and Bloodhound, as well as some of the intermediate size breeds. Most people agree it is a serious problem in the first-two named breeds. There does not appear to be any association with the sex or the age of the animal. It has been reported in young adults as well as fully mature dogs. There is no doubt it can occur suddenly after eating in a previously healthy dog.

The Cause of Torsion of the Stomach

A commonly expressed explanation is that the disease is purely a mechanical twist of the stomach. The stomach, containing some comparatively heavy food material, is pictured as swinging in a pendulum-like fashion. Then, as a result of a sudden jump from a high bench or from rolling or playing, the pendulum is swung completely around the point of fixation of the stomach, the point where the esophagus passes through the diaphragm, giving rise to a twist.

This occludes both the entrance to and the exit from the stomach so that gas, which is produced in the stomach, cannot escape, giving rise to the distension.

As stated previously, there is considerable doubt concerning the validity of this explanation.

In criticism of this mechanical theory, several objections can be raised. In many cases, there is no evidence that a sudden or vigorous movement of the dog after feeding has occurred. In addition, the contents of the stomach are not such that would facilitate a pendulum-like movement. In the normal, tightly packed, abdominal cavity of the dog, the tonicity of the abdominal muscles, the shortness of the gut, and the normal absence of much gas or fluid, tend to preclude the free mobility visualized for the stomach.

In addition, it has been shown experimentally if the stomach of the dog is distended with air by means of a stomach tube, the stomach eventually twists in either a clockwise or counter-clockwise direction, depending on the position of the spleen at the onset of distension. If the previous theory is correct, there must be some factor which causes the initial distension of the stomach. This factor is not known, but it is probably due to a condition which causes atony or paralysis of the wall of the stomach associated with a large meal and then gas production. Much of the gas found in the stomach could be caused by swallowing air.

In criticism of this mechanical theory, several objections can be raised. In many cases, there is no evidence that a sudden or vigorous movement of the dog after feeding has occurred. In addition, the contents of the stomach are not such that would facilitate a pendulum-like movement. In the normal, tightly packed, abdominal cavity of the dog, the tonicity of the abdominal muscles, the shortness of the gut, and the normal absence of much gas or fluid, tend to preclude the free mobility visualized for the stomach.

In addition, it has been shown experimentally if the stomach of the dog is distended with air by means of a stomach tube, the stomach eventually twists in either a clockwise or counter-clockwise direction, depending on the position of the spleen at the onset of distension. If the previous theory is correct, there must be some factor which causes the initial distension of the stomach. This factor is not known, but it is probably due to a condition which causes atony or paralysis of the wall of the stomach associated with a large meal and then gas production. Much of the gas found in the stomach could be caused by swallowing air.

The Development of the Disease in the Dog

According to the theory that distension is the primary condition, following distension with gas, the stomach rotates in a clockwise or counter-clockwise direction. The dog is usually severely ill, and can die within one or two hours. The stomach is severely distended, the wall of the stomach is congested, and may even be deprived of blood. The spleen is also twisted and enlarged.

A second situation can occur which is not so serious; the condition is more chronic, and may last several days. Some dogs eventually become severely distended, and may die; however, many recover spontaneously.

What Causes the Death of the Dog?

This condition in the dog has a sudden onset, usually within one to two hours of eating a large meal. The dog is first breathless and, if examined closely, the abdomen is excessively large.

The dog will stand, lie still, or move only with caution. He will generally pass feces and gas so that eventually the entire gut with the exception of the stomach has been emptied. There are often attempts at vomiting although these attempts are rarely successful. In a period varying from one-half to three hours, the stomach becomes grossly distended, and there is severe dyspnea, or difficulty in breathing. The dog may live up to 36 hours but many will die within one to two hours.

There are several explanations for the rapid onset of severe signs and rapid death. It has long been suggested one of the important aspects is the stomach pressing forward on the diaphragm thus compressing the lungs so that the animal has difficulty in breathing. There is experimental and clinical evidence, however, that the rapid development of severe signs can be better explained by the pressure of the enlarged stomach on the vena cava, the large vein which carries blood to the heart from the abdomen and hind legs. As a result of this pressure, there is an inadequate amount of blood returning to the heart, which cannot function effectively as a pump, and therefore, the blood pressure of the animal falls. This produces shock and rapid death. Other factors contribute to a lessor degree to the development of the clinical signs. There is a loss of fluids and electrolytes from the body into the distended gut, and there probably is some pressure by the distended stomach on the lungs, interfering with their function.

It can be seen from this discussion of the cause of death in torsion of the stomach, that the first priority in the treatment of torsion of the stomach must be relief of the distension.

According to the theory that distension is the primary condition, following distension with gas, the stomach rotates in a clockwise or counter-clockwise direction. The dog is usually severely ill, and can die within one or two hours. The stomach is severely distended, the wall of the stomach is congested, and may even be deprived of blood. The spleen is also twisted and enlarged.

A second situation can occur which is not so serious; the condition is more chronic, and may last several days. Some dogs eventually become severely distended, and may die; however, many recover spontaneously.

What Causes the Death of the Dog?

This condition in the dog has a sudden onset, usually within one to two hours of eating a large meal. The dog is first breathless and, if examined closely, the abdomen is excessively large.

The dog will stand, lie still, or move only with caution. He will generally pass feces and gas so that eventually the entire gut with the exception of the stomach has been emptied. There are often attempts at vomiting although these attempts are rarely successful. In a period varying from one-half to three hours, the stomach becomes grossly distended, and there is severe dyspnea, or difficulty in breathing. The dog may live up to 36 hours but many will die within one to two hours.

There are several explanations for the rapid onset of severe signs and rapid death. It has long been suggested one of the important aspects is the stomach pressing forward on the diaphragm thus compressing the lungs so that the animal has difficulty in breathing. There is experimental and clinical evidence, however, that the rapid development of severe signs can be better explained by the pressure of the enlarged stomach on the vena cava, the large vein which carries blood to the heart from the abdomen and hind legs. As a result of this pressure, there is an inadequate amount of blood returning to the heart, which cannot function effectively as a pump, and therefore, the blood pressure of the animal falls. This produces shock and rapid death. Other factors contribute to a lessor degree to the development of the clinical signs. There is a loss of fluids and electrolytes from the body into the distended gut, and there probably is some pressure by the distended stomach on the lungs, interfering with their function.

It can be seen from this discussion of the cause of death in torsion of the stomach, that the first priority in the treatment of torsion of the stomach must be relief of the distension.

Management of the Dog with Torsion of the Stomach

This is one of the true emergencies in veterinary medicine, and treatment must be instituted immediately if the animal is to survive. If the dog cannot be treated immediately by a veterinarian, the owner may be forced to render first aid to his dog. This is difficult, and there is no uniformly successful method to relieve the distension. In some dogs, a stomach tube can be passed. This can be done by the owner. Unfortunately, it is not possible to do this in dogs with major torsion of the stomach since the entrance into the stomach is obstructed by the twist in the esophagus. Some owners puncture the stomach with a large-bore needle so that the gas will escape. It is probably best to do this on the right side of the dog over the point of greatest distension. Again, unfortunately, this is not always successful. The needle can become obstructed by stomach contents, and there maybe a leakage of fluids and gas into the abdominal cavity with risk of peritonitis. If the animal is severely affected, the owner may have no choice but to attempt one of these methods to relieve the distension.

The dog should be treated by a veterinarian as soon as possible. Unfortunately, there has been insufficient experimental work done by veterinarians on the treatment of torsion of the stomach, and opinions vary on the correct form of therapy.

Many veterinarians advise immediate anesthesia and surgery to relieve the distension and the twist of the stomach. If large volumes of fluids and electrolytes are given by intravenous injection before and during the operation, reasonably good results can be expected.

More satisfactory results have been obtained by a method in which the distension is relieved by a simple surgical procedure. This is later followed by correction of the torsion when the dog is no longer in shock and better able to withstand anesthesia and surgery. This is the method recommended by this author. A small opening is made into the stomach using a local anesthesia. The wall of the stomach is sutured to the skin so that leakage into the abdominal cavity with subsequent peritonitis cannot occur. Fluid and electrolytes are given by intravenous injection; surgery is performed later to close the hole in the stomach and reposition the stomach, if necessary.

Strict control of food and water intake for many days after surgery is needed to avoid a recurrence of the condition.

This is one of the true emergencies in veterinary medicine, and treatment must be instituted immediately if the animal is to survive. If the dog cannot be treated immediately by a veterinarian, the owner may be forced to render first aid to his dog. This is difficult, and there is no uniformly successful method to relieve the distension. In some dogs, a stomach tube can be passed. This can be done by the owner. Unfortunately, it is not possible to do this in dogs with major torsion of the stomach since the entrance into the stomach is obstructed by the twist in the esophagus. Some owners puncture the stomach with a large-bore needle so that the gas will escape. It is probably best to do this on the right side of the dog over the point of greatest distension. Again, unfortunately, this is not always successful. The needle can become obstructed by stomach contents, and there maybe a leakage of fluids and gas into the abdominal cavity with risk of peritonitis. If the animal is severely affected, the owner may have no choice but to attempt one of these methods to relieve the distension.

The dog should be treated by a veterinarian as soon as possible. Unfortunately, there has been insufficient experimental work done by veterinarians on the treatment of torsion of the stomach, and opinions vary on the correct form of therapy.

Many veterinarians advise immediate anesthesia and surgery to relieve the distension and the twist of the stomach. If large volumes of fluids and electrolytes are given by intravenous injection before and during the operation, reasonably good results can be expected.

More satisfactory results have been obtained by a method in which the distension is relieved by a simple surgical procedure. This is later followed by correction of the torsion when the dog is no longer in shock and better able to withstand anesthesia and surgery. This is the method recommended by this author. A small opening is made into the stomach using a local anesthesia. The wall of the stomach is sutured to the skin so that leakage into the abdominal cavity with subsequent peritonitis cannot occur. Fluid and electrolytes are given by intravenous injection; surgery is performed later to close the hole in the stomach and reposition the stomach, if necessary.

Strict control of food and water intake for many days after surgery is needed to avoid a recurrence of the condition.

Prevention

The treatment of torsion of the stomach is unsatisfactory for two reasons. First, the condition develops so quickly that the animal can die in such a short time that many dogs die before treatment can be instituted. Second, it is not possible to save all animals with any of the presently accepted forms of treatment. Using the method in which the distension is relieved and the torsion corrected at a later date, it is expected that 75 to 80 % of dogs should survive. Some dogs are so close to death before treatment that they cannot be saved, and in others, the stomach wall is severely injured by lack of blood supply so that recovery cannot occur.

Therefore, we should direct our attention to prevention of this condition. Unfortunately, there are not generally accepted methods for prevention, and much investigative work is needed.

In some large populations of dogs, such as those in the armed forces, a high incidence of torsion of the stomach has been seen with certain feeding regimens. In many cases, the condition disappears when these dogs are given food ad lib., that is, the dogs have access to a large amount of food so that the dog may eat a small amount of food on many occasions during the day. Obviously, with this management system, the dog has no incentive to eat one large meal at any given time and he does not eat hurriedly.

The most common advice given to owners of large breed dogs is based on experiences such as the one described previously. If there is a high risk, it is best to avoid one large meal per day. The dog should be fed at least twice daily; he should be discouraged from eating rapidly, and he should not be allowed to play actively before and after feeding. The dog should have access to water continuously so there is less chance he will drink a large amount immediately after eating.

It seems there is a high risk of torsion of the stomach if the animal is given one feeding a day, the dog is allowed to drink and to indulge in vigorous exercise after eating. All these factors should be avoided.

Certain drugs that alter the mobility of the gastrointestinal tract have been advocated to prevent gastric torsion. There is no experimental or clinical evidence that any of the presently available drugs is useful. An operation known as pyloroplasty has been advocated by some to increase the size of the exit opening in the stomach. Again, there are no reports in the scientific literature that this procedure should be used.

The treatment of torsion of the stomach is unsatisfactory for two reasons. First, the condition develops so quickly that the animal can die in such a short time that many dogs die before treatment can be instituted. Second, it is not possible to save all animals with any of the presently accepted forms of treatment. Using the method in which the distension is relieved and the torsion corrected at a later date, it is expected that 75 to 80 % of dogs should survive. Some dogs are so close to death before treatment that they cannot be saved, and in others, the stomach wall is severely injured by lack of blood supply so that recovery cannot occur.

Therefore, we should direct our attention to prevention of this condition. Unfortunately, there are not generally accepted methods for prevention, and much investigative work is needed.

In some large populations of dogs, such as those in the armed forces, a high incidence of torsion of the stomach has been seen with certain feeding regimens. In many cases, the condition disappears when these dogs are given food ad lib., that is, the dogs have access to a large amount of food so that the dog may eat a small amount of food on many occasions during the day. Obviously, with this management system, the dog has no incentive to eat one large meal at any given time and he does not eat hurriedly.

The most common advice given to owners of large breed dogs is based on experiences such as the one described previously. If there is a high risk, it is best to avoid one large meal per day. The dog should be fed at least twice daily; he should be discouraged from eating rapidly, and he should not be allowed to play actively before and after feeding. The dog should have access to water continuously so there is less chance he will drink a large amount immediately after eating.

It seems there is a high risk of torsion of the stomach if the animal is given one feeding a day, the dog is allowed to drink and to indulge in vigorous exercise after eating. All these factors should be avoided.

Certain drugs that alter the mobility of the gastrointestinal tract have been advocated to prevent gastric torsion. There is no experimental or clinical evidence that any of the presently available drugs is useful. An operation known as pyloroplasty has been advocated by some to increase the size of the exit opening in the stomach. Again, there are no reports in the scientific literature that this procedure should be used.

Signs

Bloat is one of the most common life-threatening conditions a dog can face, yet many pet parents are unfamiliar with it.

Also known as gastric dilation-volvulus (GDV), bloat occurs when a dog's stomach becomes distended and filled with air, food or another liquid and presses against the other organs in his abdomen.

Bloat can also cause the stomach to twist, which can cut off the blood supply to the stomach and also prevent it from emptying. Bloat requires immediate medical attention and can be deadly -- killing anywhere from 25 to 40 percent of the dogs it strikes.

Signs of Bloat in Dogs

It's very important to be aware of the symptoms of bloat, because if your dog exhibits them, immediate medical attention is required.

Signs can include a distended or swollen abdomen, an abdomen that sounds hollow when you tap it with your finger, abdominal pain or discomfort, retching or an inability to belch or vomit, excessive drooling, shortness of breath, rapid heartbeat, cold body temperature, pale gums, weakness and even sudden collapse.

Bloat is one of the most common life-threatening conditions a dog can face, yet many pet parents are unfamiliar with it.

Also known as gastric dilation-volvulus (GDV), bloat occurs when a dog's stomach becomes distended and filled with air, food or another liquid and presses against the other organs in his abdomen.

Bloat can also cause the stomach to twist, which can cut off the blood supply to the stomach and also prevent it from emptying. Bloat requires immediate medical attention and can be deadly -- killing anywhere from 25 to 40 percent of the dogs it strikes.

Signs of Bloat in Dogs

It's very important to be aware of the symptoms of bloat, because if your dog exhibits them, immediate medical attention is required.

Signs can include a distended or swollen abdomen, an abdomen that sounds hollow when you tap it with your finger, abdominal pain or discomfort, retching or an inability to belch or vomit, excessive drooling, shortness of breath, rapid heartbeat, cold body temperature, pale gums, weakness and even sudden collapse.